Last year, a team of US-based researchers demonstrated an origami-style battery that could produce small amounts of electricity using dirty water. The team has now given its bacteria-powered device a boost, tweaking the design to resemble an origami ninja star and upping the power density in the process.

Researchers at the Binghamton University in New York developed their origami battery with a view to powering low-energy devices where electricity isn’t so readily available. Powered by the bacteria in a few drops of dirty water through the process of bacterial metabolism, the paper-based battery could be built to run a biosensor in the field at a cost of just five US cents.

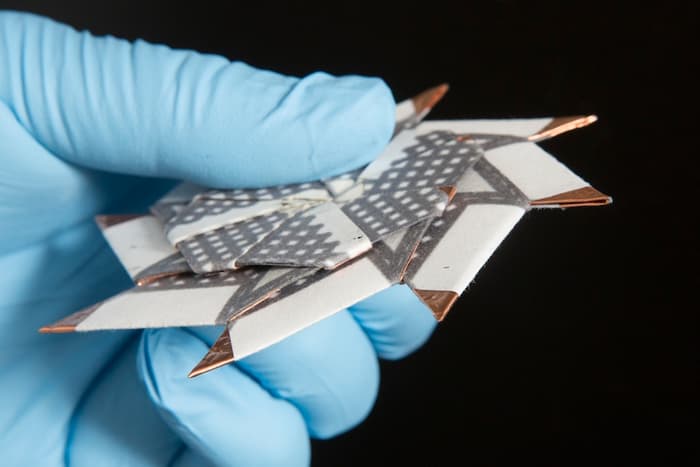

Where the original design folded up like a matchbook with four modules laid on top of one another, the latest iteration packs eight batteries into a sliding, star-shaped frame. Within each of the modules are paper layers, an anode, proton exchange membrane and an air-cathode, while in the center is an inlet where the dirty water is fed.

As the battery is pulled apart into a donut-shape, fluidic pathways running through the paper layers carry the water into the eight fuel cells and kick off the electricity-producing chemical reaction. This state also allows the separate battery modules to connect with one another, which improves power output and also exposes the air-breathing cathodes to the air.

“Last time, it was a proof of concept,” says Seokheun Choi, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Binghamton University. “The power density was in the nanowatt range. This time, we increased it to the microwatt range. We can light an LED for about 20 minutes or power other types of biosensors.”

Using a low-cost battery like this to power pregnancy and HIV tests could greatly expand access to these kinds of medical devices. While paper-based versions of these are available, the researchers claim that they aren’t as sensitive as the more sophisticated electrochemical and fluorescent versions, but other sources of power aren’t always practical.

“Commercially available batteries are too wasteful and expensive for the field,” says Choi. “Ultimately, I’d like to develop instant, disposable, accessible bio-batteries for use in resource-limited regions.”

While the performance enhancement is promising, the more intricate design does come at a price. Where the original cost around five cents, the ninja star version costs around 70 cents to produce. This is because a carbon cloth is used for the anode along with copper tape, compared to pure filter paper in the original. The team is now working to develop a fully-paper-based device with the same power density of the ninja star design but at a lower cost.